Music

Creative

Home | Help | Contact Us | Useful Links | Terms of Use | MP3 Archive

THE RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER

A space-time interpretation by Richard Hill

"I think your space time ideas are entirely plausible and would have interested Coleridge."

John Carey, Merton Professor of English Literature, Merton College, Oxford University, England.

'Down dropt the breeze, the sails dropt down'

Samuel Taylor Coleridge's legendary and profound poem, written over 200 years ago, can be freshly illuminated for modern audiences by interpreting it in the genre of Star Trek or other comparable contemporary space mythology. In Richard Hill's space time interpretation of The Rime, the Ancient Mariner is seen as a lone messenger visiting many universes. This ancient, time-travelling humanoid is locked into a never ending mission - to force others, in this case a hapless wedding guest, to learn the consequences of disturbing the balance of inter-relationships within the natural world. The Mariner brings a message from the past to the present about the future and having delivered it, moves on to repeat the cycle endlessly. This space time drama is not just a good story - it also has a deep and significant message for our present relationship with our planet Earth.

The subject of spirits, daemons of earth or middle air, or of the elements, was socially discussed in Coleridge's time and such 'invisible inhabitants of this planet' are freely mentioned in the margin gloss of the poem as well as in this text, used as an introduction to it, by Thomas Burnet in his Archaeol. Phil., p.68.

' I can easily believe that there are more invisible than visible natures in the universe. But who shall describe their family? Who set forth the orders, kinships, respective stations and functions of each? What do they do? Where is their habitation? The human mind has always sought after, but never attained, knowledge of these things. Meanwhile it is desirable, I grant, to contemplate in thought, as if in a picture, an image of a greater and better world; lest the mind, accustoming itself to the minutiae of daily life, should become too narrow, and lapse into mean thoughts. But at the same time we must be vigilant for truth, and set a limit, lest we fail to distinguish certain from uncertain, day from night.'

Life at another level of existence is therefore openly woven into the fabric of the poem. But it is what Coleridge's intuition did with these imaginary beings and indeed, what he did with the known laws of physics by which we exist and perceive our surroundings, that so startlingly matches our modern speculations about parallel universes and space time travel.

There are many clues within the poem to lead us to the notion that Coleridge imagined his 'old navigator' (as he later called the Mariner) to have knowledge both of a connected parallel universe and of time travel, even though there were no words to describe such ideas in the late eighteenth century. Even today these theories are at the extreme boundary of scientific speculation, but they are also persistent archetypes, featuring in many a science fiction narrative. In The Rime, it is the presence of these very same archetypes which drive the poem and allow a space time treatment of the work to be created so naturally.

In Coleridge's narrative, the 'Argument' at the beginning of the poem sets the stage:-

'How a ship having passed the Line was driven by storms to the cold Country towards the South Pole; and how from thence she made her course to the tropical Latitude of the Great Pacific Ocean; and of the strange things that befell; and in what manner the Ancyent Marinere came back to his own Country.'

The 'strange things that befell' are the keys which open the door to the otherworldly and archetypal elements which pervade the poem. Of course in such a great work as The Rime there are a number of themes - the relationship between the Christian and pagan elements is a fascinating study all on its own - and there is an overarching message of deep concern and love for the natural world which powers the poem, evidence of Coleridge's broad and intuitive understanding of how the whole universe must be inter-related. But it is in the location of the events, the distortion of physical laws and in the company of the strange entities which populate the poem that we feel we are not on planet Earth at all. This is a different, at times terrifying but still wondrous space time continuum.

Let us take a journey though the poem and see what Coleridge actually tells us about this other universe and its inhabitants. The 'alien' events really begin after the albatross, a bird of good omen, has been thoughtlessly shot and the ship becomes becalmed in the Pacific, near the Equator. But long before that - in fact in the very first word of the poem, Coleridge lets us know that this story is not going to obey the known laws of physics.

'It is an ancient Mariner'

This blunt, oddly chosen, paradoxical opening phrase has a companion at the end of the poem, where Coleridge tells us

'The Mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone'

Why choose 'It' instead of 'He is an ancient Mariner', and 'Whose beard with age is hoar Is gone' instead of 'has gone:' The inference seems clear - these lines imply instant appearance and disappearance - as if a transporter device straight out of Star Trek is being used to materialise the Mariner. Further, the use of the word 'It' to start the poem suggests that the Mariner is not totally human. This is reinforced by his use of hypnosis to force the wedding guest to listen to him. But it is not hypnosis as we know it, because it is achieved by the physical power coming from his 'glittering eye', an attribute which is referred to throughout the poem, sometimes with a different description, as in the phrase 'The bright-eyed Mariner.' Again, this is an alien and archetypal trait well-known to fans of contemporary space mythology. It seems we have here an ancient humanoid being who has survived beyond countless human life spans, acquired superhuman and irresistible power and who can appear and disappear at will. Sounds like this could be the start of an excellent sci-fi adventure!

As the story develops, the helpless, hypnotised wedding guest is made to witness the entire sequence of events, including the needless slaughter of the innocent, wandering albatross, after which the ship is becalmed. It is in this part of the poem that we first seem to be going through a strange transformation of location, perhaps into a parallel universe. On what evidence? Well, the sea itself changes consistency 'The very deep did rot' - and what are the 'slimy things with legs' that crawl upon it? Of course there are natural explanations - a Sargasso-like Sea, sea snakes, phosphorescent plankton - and the 'death-fires' that danced at night can be interpreted as St. Elmo's fire, but the fact that some of the crew are now having collective dreams of 'the Spirit that plagued us so' following the ship 'nine fathom deep', starts to stretch these reality based interpretations. And when 'a something in the sky' appears and turns out to be a craft that can sail 'without a breeze, without a tide', we are surely in the presence of alien technology. This visit of the death-ship, with its strange, nightmarish crew of two, the man Death and the horribly beautiful woman Life-in-Death are all one could wish for in a pair of terrifying aliens. The sudden departure of this vessel reinforces the argument that we are in another universe, with different rules to our own:-

'The sun's rim dips; the stars rush out:

At one stride comes the dark;

With far-heard whisper, o'er the sea,

Off shot the spectre-bark.'

Again and again throughout the poem, Coleridge plays with time like this. The action described in the above quote happens impossibly fast, almost like a piece of modern television or film editing and the incredible speed with which the death-ship leaves the scene only adds to our sense of being in another continuum. The pattern is now set for the rest of the poem. Complete with film-like, flashback sequences of the wedding guest under the power of the Mariner's glittering eye, the story evolves in this different, frightening yet at times beautiful, new world. The crew, apart from the Mariner, appear to die from thirst, but their bodies are reactivated by alien entities and are able to sail the ship, 'yet never a breeze up-blew'. The mysterious Polar Spirit ('and it was he That made the ship to go') delivers the vessel to what we could nowadays describe as two guardians of a space time portal, or wormhole, which leads to the way home. These ethereal beings, the Voices in The Air, act as escorts to the ship as, in one of the most startling and futuristic sequences in the poem, Coleridge describes what, to the crew of the star ship Voyager, would obviously be a space time journey.

'But why drives on that ship so fast,

Without or wave or wind?'

'The air is cut away before,

And closes from behind.'

There is a shot in the title sequence of 'Star Trek - Voyager' which depicts the space ship cruising among star systems at incredible speed, encased in its own 'warp bubble' which can be seen dividing at the bow and closing at the stern, exactly as Coleridge conceived for his own ship some 200 years ago. In the margin gloss, we are told that the speed of his ship is 'faster than human life could endure' and he puts his Mariner into a trance to survive it, in perfect archetypal space mythology style.

When the Mariner's ship is returned to its own continuum the alien entities leave the bodies of the crew and return to their own universe in a display of coloured light that would grace any of Steven Spielberg's close encounters with extra-terrestrials:

'And the bay was white with silent light,

Till rising from the same,

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

In crimson colours came.'

And three verses later:

'They stood as signals to the land,

Each one a lovely light;'

As these entities of light depart, the Mariner's ship is sunk by an earthquake, or in sci-fi terms it may be a final temporal boom from the other universe. The Mariner now returns, with the wedding guest, to the very same wedding celebrations at which he materialised at the start of the poem. Hardly any time has passed, a known phenomenon related to travelling at around the speed of light. He delivers his final message of love and respect for life on our planet, urging us to restore the balance of nature which we have so thoughtlessly and catastrophically upset:

'Farewell, farewell! but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding -Guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.'

And now the Mariner is gone. Who knows where? He leaves behind a lesson for humankind, through the medium of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the brilliant 26 year old visionary poet who saw beyond his own world and into the future of us all.

Richard Hill

Text & Spelling Resource - The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Published by Harper & Brothers, 327-335 Pearl Street, Franklin Square, New York - 1884. Illustrated by Gustave Dore.

<<back to Rime home page

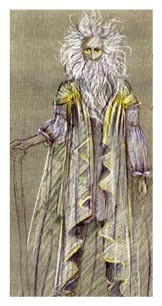

Designs for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner project are the copyright of Paula Kenevan and Simon Kenevan. See Terms of Use.

Home | Help | Contact Us | Useful Links | Terms of Use | MP3 Archive

Copyright ©2023 Richard Hill. Site design by Paul Hill.